San Francisco is a city that rewards looking closely, under the surface, behind the closed curtains and doors. It’s so closely associated with its shroud of fog for a reason. This is a mysterious city that defies easy characterization, much less caricature. San Francisco provides the only possible setting for America’s preeminent mystery book, The Maltese Falcon. And the city is mysterious in other ways as well: there are things here that are inexplicably quirky or bizarre, are not obvious, not easy to spot, hidden from view if you don’t know exactly where to look, or here one minute and gone the next.

Witness, if you will, The Triumph of Light, a story almost too good to be believed.

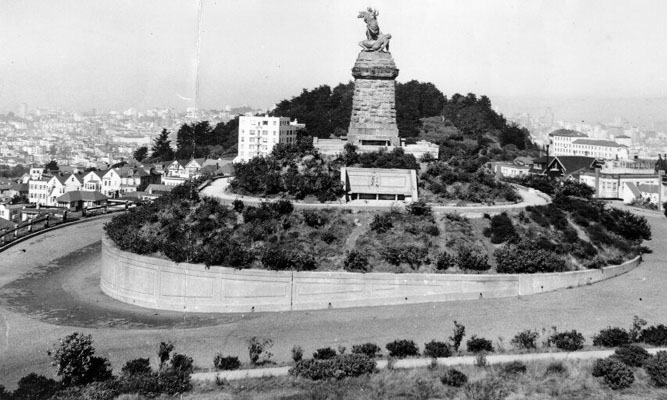

In the late 1880s, during the days when such monuments were erected, Adolph Sutro, a silver baron, philanthropist and former mayor who owned the hill at the precise geographic center of the city, decided to commission Belgian artist Atoine Wiertz to build an allegorical piece depicting the victory of liberty, depicted as a torch-carrying lady, over despotism, a cowering muscled hulk. And so it was completed, installed and dedicated on Thanksgiving Day, 1887. At the dedication ceremony, Sutro said: “May the light shine from the torch of the Goddess of Liberty to inspire our citizens to good and noble deeds for the benefit of mankind.”

So, the statue stood, looking over the people of San Francisco, possibly guiding them toward good and noble deeds. And in many other places, that might have been the end of the story but, hey, this is San Francisco and we don’t roll that way.

Years passed, and people stopped thinking in the ways Sutro and others thought they ought. Monuments to liberty and other civic virtues were no longer objects of public affection and care. Ugly apartment blocks and condominiums were built around this statue’s site, blocking its commanding view and removing the piece from public view and consciousness. Fewer and fewer San Franciscans, as time passed, even knew of the monument’s existence.

There were natural forces at play too. As it turns out, statues need love and care. Their materials decay and degrade over time. The Triumph of Light was no exception. The San Francisco Arts Commission reported that the statue was in danger and there was serious talk about replacing it with a Bufano sculpture the city had in storage.

That was the near-final public record of the statue. And then, sometime in the 1950s, poof, The Triumph of Light simply disappeared. No one, not neighbors, not the city government, knows where. What’s left now is the base and the pedestal. Its inscription is worn down to virtually nothing.

Another San Francisco mystery.

Few people know of the contributions Sutro made to the City, and a few of them still exist. These days, with corporate greed and corruption at an all time high, it’s worth looking back on a the life of this millionaire and learning what he did with his fortune. Most may know about the Cliff House and Sutro Baths, but he was also responsible for the streetcars that used to go down Geary to the beach, and all the trees that are growing on Mt. Sutro and the Presidio. This is not to forget all his generosity toward the poor and the common working families. The Cliff House and Sutro Baths, in fact, were not built as a rich man’s playground, but were intended for working families to have an inexpensive and pleasurable place to spend the weekend. Even the grounds and gardens surrounding his long-gone home overlooking the Cliff House were open to ordinary people. He designed them in a style similar to formal gardens found around stately European mansions and placed plaster copies of famous statues throughout the area to edify the public, since few people in that time could afford a Grand Tour of Europe. The sad part of all this is, like the Triumph of Light, most of what he built was erased. His home, the gardens, the baths and adjoining facilities are all gone. Still, the trees remain, so Sutro’s “green” legacy lives on.

Thanks, Marc. What a great legacy to remember.

Had some old-timers and history buffs dig up some info for you:

http://outsidelands.org/cgi-bin/mboard/stories2/thread.cgi?2190,0#msgtitle

Tammy,

That is really interesting. The more you dig, the more you discover. God, we live in a weird town!

Brent

BTW, Tammy, here’s something else about growing up in San Francisco, you might like; today’s post: https://sanfranciscoba.wordpress.com/2012/06/08/know-your-neighbors/

Oh yes, the topic of Mr. LaVey (one of the best self-promoters this side of P.T. Barnum) has been beaten to death in several fb groups. Alas I was so sheltered I never knew about this while it was going on. Good write-up a couple years ago here: http://richmondsfblog.com/2010/06/09/the-richmond-districts-satanic-past/

Does the main sculpture still exist somewhere?

It’s a mystery. No one knows.

You still have the opportunity to visit the Wiertz Museum in Brussels https://www.brusselsmuseums.be/en/museums/wiertz-museum

or visit Dinant (birth place of Wiertz) where a original replica of the sculpture still is in a park.

Antoine Wiertz died in 1865, so Sutro could not have commissioned it from him, but I believe that a large-scale version was created posthumously for an exposition somewhere in Europe in the 1880s. At some point there was a group trying to erect a monumental copy that would perch on the cliff above Dinant, sadly never realized. (The replica mentioned in the previous post is puny by comparison.)

Wiertz was a full-on megalomaniac who sought fame in his lifetime, and he was big on self-promotion; upon his death, his studio became a museum, which he assumed would further his reputation for posterity. While the museum still exists, it is literally overshadowed by the European Union’s main building. Many Brussels residents have never heard of it, let alone visit it. Wiertz did derive some fame insofar as his museum became a tourist attraction particularly popular with British and American visitors in the late 19th-early 20th centuries, and it’s possible this is where Sutro first saw the sculpture.

Wiertz was also aligned with liberal thinkers in his time, and was an advocate of free thought. 19th-century Belgian politics were informed by Freemasonry, so that may also have influenced Sutro, although I don’t know if he was a Mason. Wiertz also had something of an afterlife in the pacifist community, and Stanford University president David Starr Jordan referred to work by the artist in speeches in that context some years later, furthering the Belgian’s presence in the minds of Northern Californians.

I think “Weird Tony” Wiertz was a more apt choice for San Francisco than Sutro ever knew. And note that this sculpture predates Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty, which was a gift of state, not of philanthropy, which makes SF’s Triumph all the more remarkable.

Brilliant. Thank you so much for adding this amazing backstory.