[Portions of this post were originally written in 2010.]

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before; the storyline is likely to be sadly familiar.

A man with big guns and an even bigger grudge walks into a place of business and starts shooting, first at particular people, later indiscriminately, finally to kill himself. The weapons he used were purposefully designed to throw as many bullets as possible in a short amount of time; in other words, they were built to kill lots of people really fast. That is, of course, why he’d purchased them.

In this particular case, the man used two TEC-9s, like the one in this photo (below).

The man in this particular case, Gian Luigi Ferri, was angry at a law firm located in the 101 California Street building in San Francisco. His first bullets were directed at some lawyers from the firm but after his blood lust was stirred, he went to other floors and shot pretty much randomly.

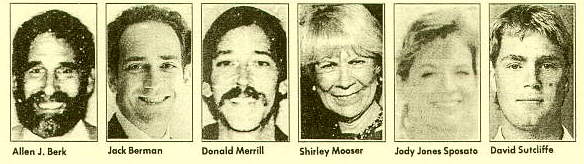

It was on one of these other floors that Ferri shot and killed my friend Mike Merrill. (His first name was actually Donald (see above), but everyone called him Mike.) I’d seen Mike for the final time, as it turned out, a very short while before, at my father’s funeral. After the service, Mike came over to me, fixed me with his bright, intense, crystal-blue eyes and told me what a great guy my dad had been.

Just a few months later, I was at his funeral saying roughly the same thing to his widow.

Following the 101 California Street shootings, and the national media attention it attracted, some gun laws tightened: centralized data bases were established to screen potential buyers, limits were placed on large-capacity magazines, certain models were made unavailable to civilians. None were serious steps, but legislation and regulation were, it seemed, moving in a constructive direction.

In the intervening 20 years, with the passage of time and fading of memory, many of the laws and regulatory schemes created in the wake of this particular tragedy have been loosened or have expired, especially in some states. To some, the problem isn’t the gun but the person using it; regulating gun ownership and use is shooting, as it were, at the wrong target.

I very strongly believe the opposite.

West Churchman, a great mentor of mine, believed that tools were not value-neutral. You get a shovel to dig with; if you don’t want stuff dug up, you shouldn’t get one. If the act of digging disturbs what you value – like, for example, a wilderness – then the shovel itself, by virtue of its design and its very reason for being, has an ethical consequence.

West would never have subscribed to the theory that “guns don’t kill people – people kill people.” Like all other tools, guns were specifically created to perform a certain function, and its particular function has significant moral weight. In the case of handguns, their purpose is to shoot people, in no way a value-neutral function. In the case of automatic assault weapons (like Ferri’s MAC-9), their purpose is also to shoot people, but a lot more people and really fast. Having a handgun or an assault rifle prepares you to kill – purposefully and with designed efficiency. Not just using one, but also owning one has moral implications.

People have said, if someone wants to kill, a knife works too. True enough, in a single instance. But to kill many people with a knife takes almost unimaginable time, physical strength and proximity. Killing many people with an automatic assault rifle is a physically trivial exercise.

Take away the gun, take away the tool.

![san-francisco-fog (5)[2]](https://speakingplainly.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/san-francisco-fog-52.jpg?w=840)